I want more life, fucker

The universe is a tricky mistress. As permanent and absolute as she appears, the contrary holds true. Take for example the multiverse theory. Previously limited to pulp sci-fi novels, the concept has now penetrated global consciousness.

This is due to two things:

Culturally - comic book movies frequently use the multiverse to escape narrative dead ends.

Scientifically - through the study of quantum physics and string theory, we are slowly but surely learning how much we don’t know.

While the multiverse concept is entertaining in movies and mind-bending in scientific papers, we have not yet experienced it in a real world(s) scenario.

Or have we?

Reality has a habit of not conforming to our wishes.

What if we had already transitioned from one plane of reality to another?

What if we had done this multiple times?

Perhaps we have already experienced a bifurcation of our timeline, but without the capacity to perceive this, we remain unaware our shifting reality. Only the realm of our deeper subconscious memory would detect that something was amiss. This misalignment of perception and reality results in an unsettling feeling - the sense that something profound, or reality altering has occurred - yet we are unable to place a finger on what it actually is.

Leon Kowalski: “Nothing is worse than having an itch you can never scratch.”

To clarify this, we can ask a question:

If our reality changed, how would we know?

This is not to question the validity of reality itself. Rather, it is to explore if we transition from one timeline to another, and seek evidence to pinpoint the moment that there is a change in our established reality.

We will use Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner to answer this question, due to that same sense of enigmatic profundity which is present within the film.

We will examine the dramatic context surrounding its production - how one event fueled its fierce emotional furnace and brought the film into reality, despite the fact that it was never meant to exist.

Case in point – in the original timeline, Ridley Scott never directed Blade Runner. The timeline should have been like this:

In the original timeline, a film called ‘Dangerous Days’ - starring Dustin Hoffman, was released in 1982. While it contained a mishmash of noir and sci fi, the ugly-beautiful, northern-England inspired, old-future of Scott’s mind never existed. The result of this curious but ultimately inadequate film, was that science fiction continued on its original path - wedged between the post-scarcity, utopian ideals of Star Trek, and the science fantasy worlds of Star Wars and Flash Gordon.

There was no Blade Runner.

While it’s difficult to imagine this, we are only one event removed from it being our reality.

What forced this change? Why did we shift from the binary morality of Flash Gordon and Ming the Merciless, to the impossible ambiguity of Rick Deckard, Roy Batty and what it is to be human?

To understand this, we need to examine the event that changed Ridley Scott, and why he chose to throw himself into Blade Runner.

Prior to 1982, Scott was riding high on the success of 1979’s Alien. With critical and commercial recognition, he was primed to continue his career. However, his intention at that time was to move away from sci fi:

“With Alien, I’d just finished a science fiction picture. And here Hampton (Fancher) and Michael (Deeley) were offering me another sci-fi. I just didn’t feel that I could immediately go into yet another one of those: it was time to move on to something else.”

Ridley Scott on his initial rejection of Blade Runner – Future Noir, Paul Sammon

This post-Alien Scott went on to turn down Blade Runner (‘Dangerous Days’) to focus on expanding his directorial range.

But it’s here that the unfathomable workings of the universe came into effect. Shortly before beginning his next film, Scott’s older brother, Frank, died of cancer at the age of 45.

Bereavement is a calamitous experience, and due to our linear perception of time, we cannot know its true impact until much later. Meaningful insight only becomes accessible after the passing of time and viewing the experience as part of a larger chain of events.

The sudden death of someone close brings forth a torrent of emotions, beginning with an overwhelming sense of denial. This stems from a reluctance to accept a new reality – different from that which we have grown accustomed. This abrupt shift forces us to confront two things - the fleeting nature of existence, and by extension, our own mortality. These are difficult topics to process when we are at our most cognizant, so to confront them in a compromised emotional state is an insurmountable task. Therefore, it’s understandable that the default response to death is denial.

It’s a futile attempt to cling to a reality that we are not yet ready to relinquish.

Roy Batty: “There’s only two of us now.”

Pris: “Then we’re stupid and we’ll die!”

Roy Batty: “No we won’t.”

In Scott’s case, the untimely death of his brother disrupted his established reality to such an extent, that it altered his timeline - and ultimately, ours.

“There were… two other reasons I accepted Dangerous Days (Blade Runner’s working title), one was the fact that I knew Michael Deeley well, and knew I could work with him. The second tied in with the grief I was feeling over my brother’s death. By this time, I’d realized I needed something to get my mind off that, and that I’d better take something which would be an immediate go.”

Ridley Scott on accepting Blade Runner – Future Noir – Paul Sammon

Like those who plunge into deep work to shut out troubling thoughts, Scott focused on filmmaking to avoid confronting his brother’s death. However, when placing a lid on a can of worms, they squirm all the more in the darkness.

It was within this headspace that Scott chose to direct Blade Runner.

This emotional turmoil combined with the urge to work created a directorial intensity far beyond the likes of James Cameron or Stanley Kubrick. This can be seen in Blade Runner’s visual and thematic obsessions - reflecting not only what Scott was going through, but also what he was desperate to avoid – facing his own mortality.

Evidence of this is present throughout the film:

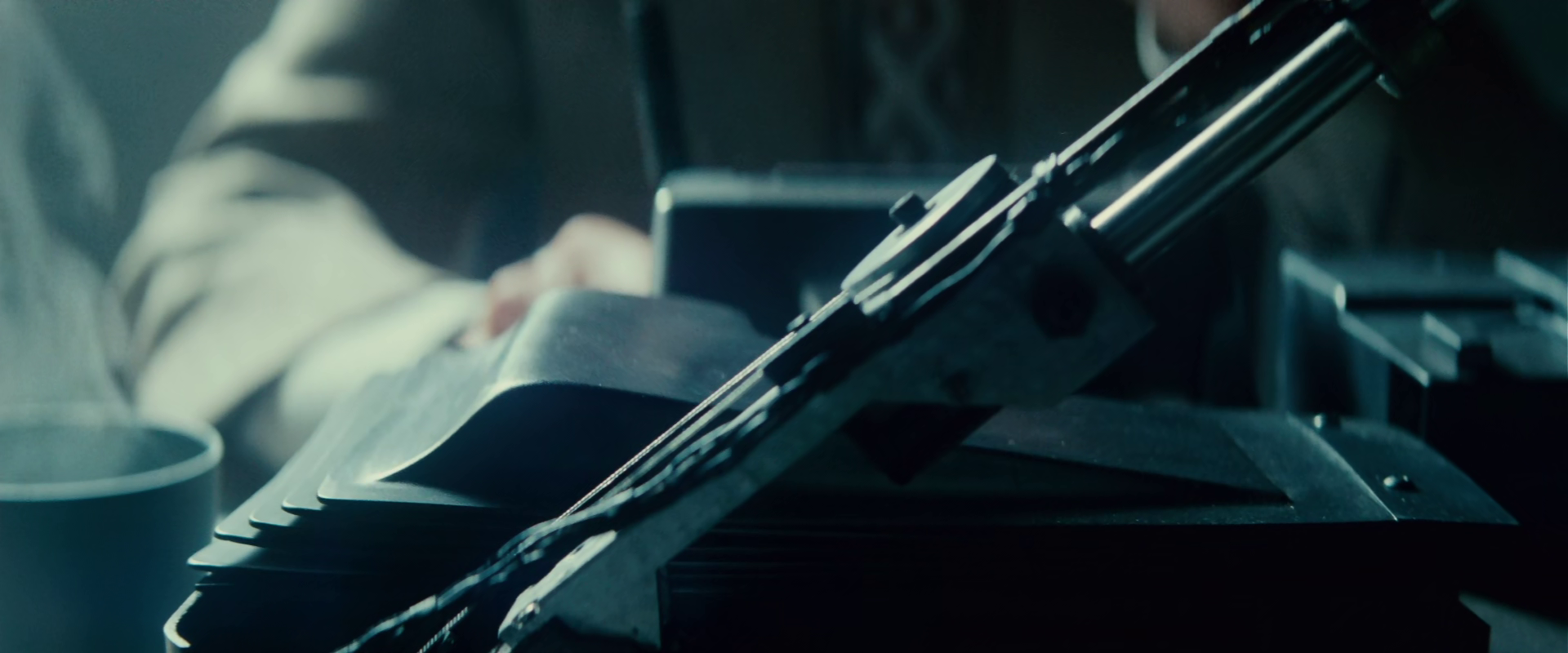

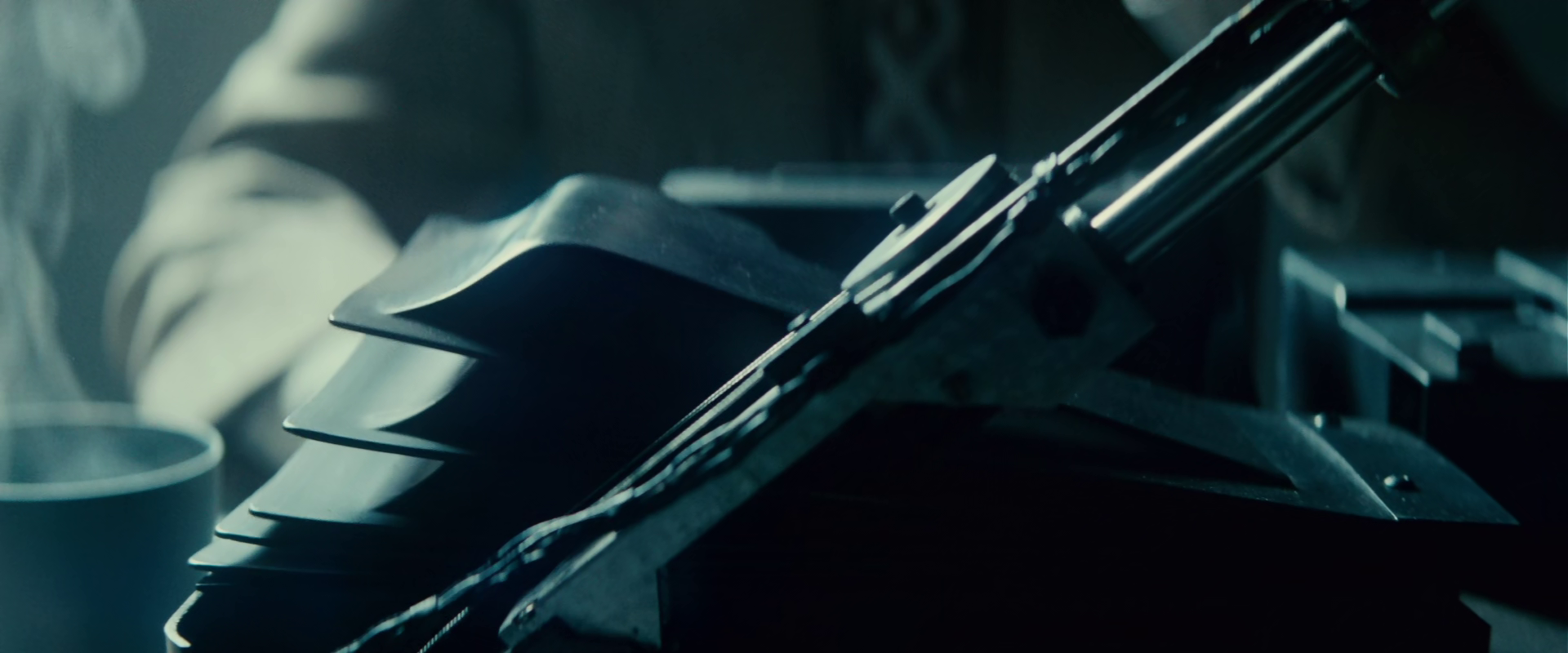

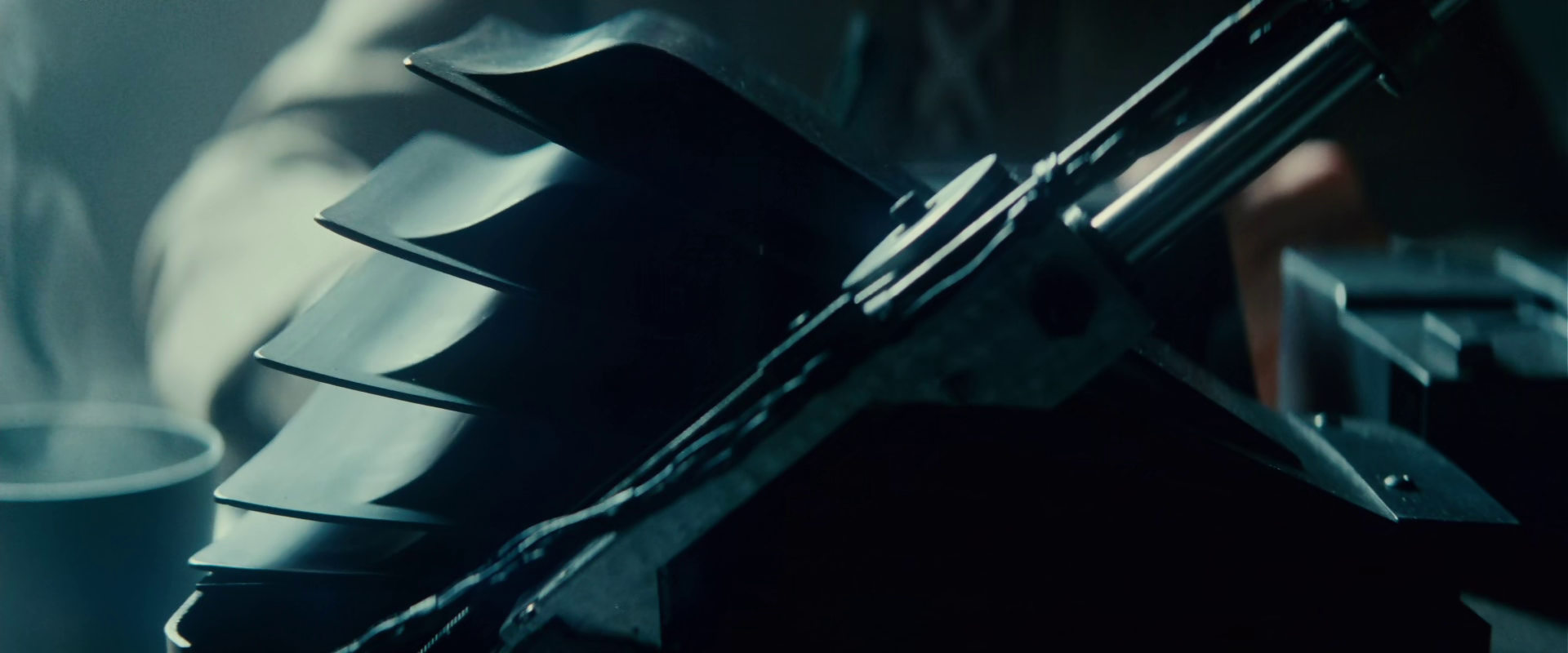

Voight Kampff machine

The look, feel and manner of the VK machine are reminiscent of a ventilator.

Los Angeles 2019

The entropy-stricken, ever present city is a key character in the film, reflecting the emotional state of those within it.

The Bradbury building

Beyond serving as the backdrop for Deckard’s showdown with Pris and Roy Batty, it is also a visual reminder of the inevitability of decay:

JR : We can’t win.

Pris : Why not?

JR : No one can win against kipple, except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment I’ve sort of created a stasis between the pressure of kipple and nonkipple, for the time being. But eventually I’ll die or go away, and then the kipple will again take over. It’s a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep – Philip K Dick

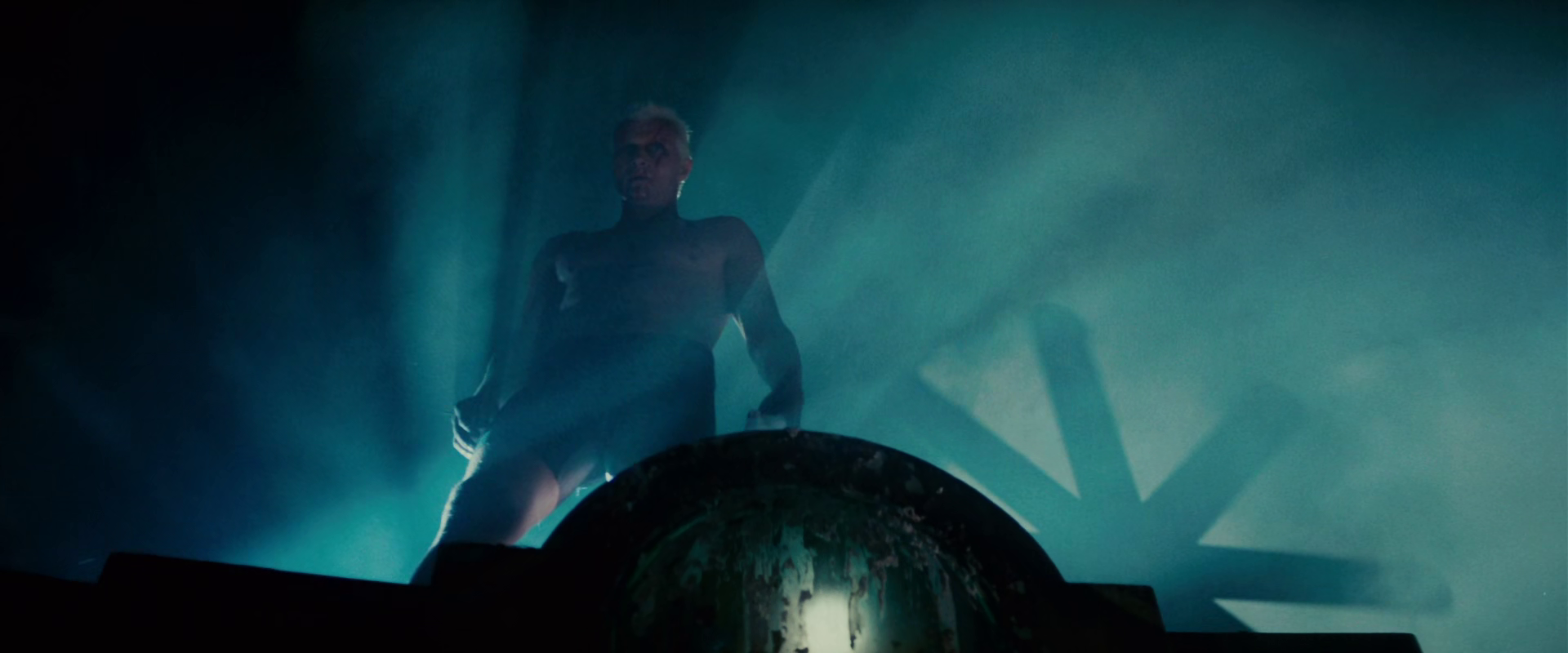

While visible throughout, a profound example of ‘kippleization’ / entropy can be seen during the rooftop finale. However, due to the emotional intensity of the scene, it is easy to miss.

Windmills

In a world of flying cars, replicants and planetary colonization, wind power is vastly outdated. Added to this, the decaying Bradbury building is dwarfed by the surrounding mega structures, thereby blocking it from any major source of wind. The juxtaposition of windmills beneath hulking corporate entities indicates meaning – gravestones marking the death of an earlier time. That the windmills were never taken down demonstrates a refusal to acknowledge a new reality.

In addition to the visuals, the thematic elements threaded throughout the film reflect Scott’s troubled state of mind:

Retirement

This euphemism demonstrates an attempt to conceal the truth of an abhorrent act – ending the life of a sentient being. Reducing murder to bureaucratic terminology is denial of reality manifest.

This distinctly human behavior is directly contrasted by the replicants’ obsession with time. It’s akin to an individual in the prime of their life being diagnosed with a terminal illness:

Leon Kowalski: “My birthday is April 10, 2017. How long do I live?”

Rachael Tyrell: “Deckard… you know those files on me? The incept date. The longevity. Those things. You saw them?”

Roy Batty: “I want more life, fucker!”

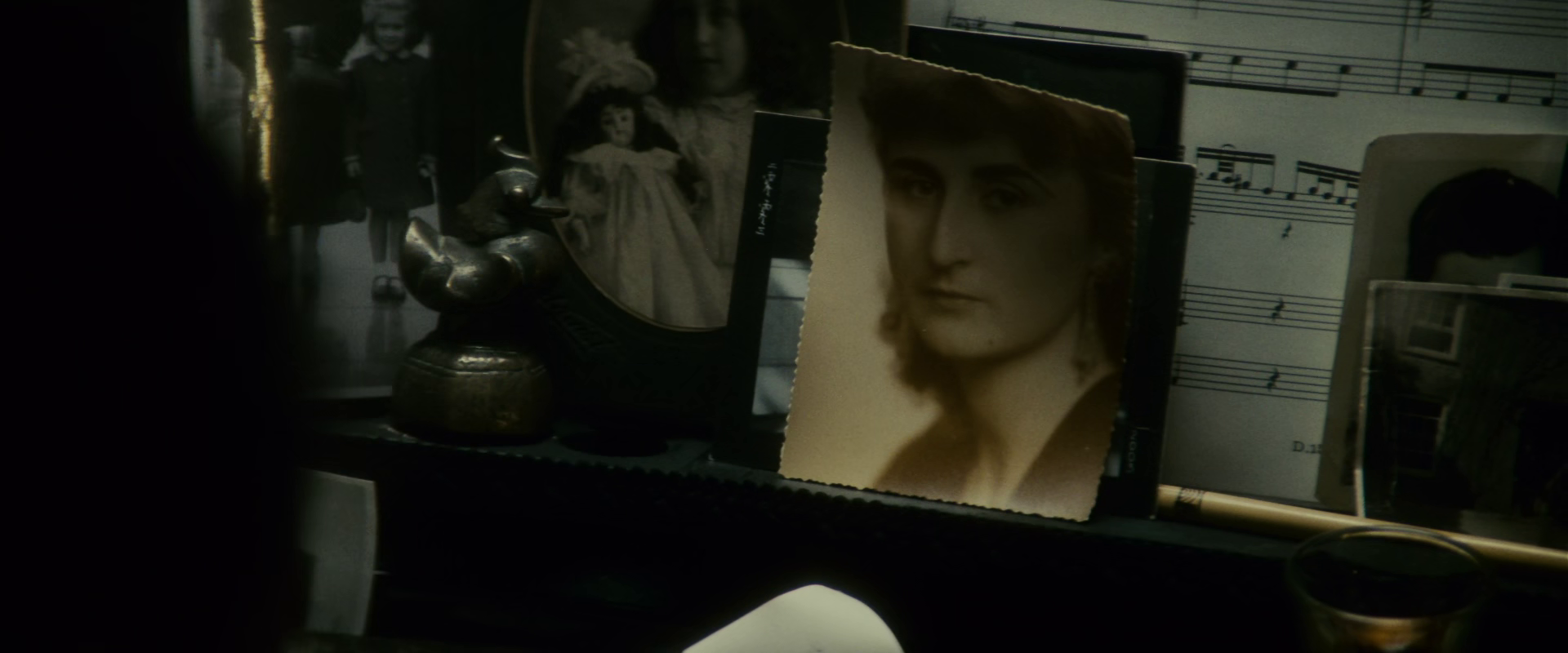

This is further expanded by the recurring motif of photos:

Roy Batty: “Did you get your precious photos?”

This fascination with the past is also reflected in the artificial animals seen throughout the film:

Both replicants and humans have a reliance on synthetic memories. This yearning for an earlier time demonstrates reluctance to let go of a departed reality – echoing Scott’s circumstances.

In looking at the above examples, we can see that Scott’s emotional state is woven into the fabric of the film, and like cigarette smoke, its presence hangs heavy in every scene.

To put it simply, Blade Runner is a film about death.

“There is a lot of death in Blade Runner. ‘Accelerated decrepitude’, as Pris would say.”

Rutger Hauer

It is here that the deeper meaning of the film can be uncovered. By illuminating Ridley Scott’s “darkness”, we can find truth amidst paradox. Take for example the Stoic concept of ‘Memento Mori’ – ‘remember that you will die’.

For a Stoic, daily contemplation of mortality creates a newfound appreciation for life. Similarly, when an individual undergoes an experience which changes them internally, it also impacts their external perceptions. It was this newfound perspective which was developed during the production of Blade Runner:

“Ridley mentioned how his brother’s death had affected his personal life. Then he said that to make a movie like we’d made, a movie like Blade Runner, took a certain kind of energy, and that it was very draining.”

Sean Young on Ridley Scott: “I Am the Business” – Paul Sammon

This is evident in the unconventional depiction of the film’s antagonist. Unlike a typical villain, he doesn’t battle against the protagonist. Instead, his opponent is his four year lifespan.

Roy Batty

Batty begins his character arc with dramatic agency to understand his planned obsolescence:

Roy Batty: “Questions…morphology, longevity, incept dates.”

This then transforms into a rage against his timebound existence, demonstrated when meeting his maker:

Roy Batty: “I want more life, fucker!”

After realizing that he cannot extend his four-year lifespan, he accepts his newfound reality. With this internal change, comes a shift in his existential outook:

Roy Batty: “All those moments will be lost in time like tears in rain…”

Here we see Batty’s ultimate understanding. Rather than fighting against his predefined mortality, he savors the taste of existence. In experiencing its fleeting beauty, he gains perspective. This internal change is what liberates him from the prison of his former thinking.

“I cannot escape death, but at least I can escape the fear of it."

— Epictetus

This brings us full circle to Ridley Scott’s experience during production. in a case of profound accord, we can see that Scott’s emotional journey occurred alongside that of Roy Batty:

“…it all was kind of an exorcism, in a way… Accepting ‘Dangerous Days’ helped get me through my brother’s passing.”

Ridley Scott on making Blade Runner: Future Noir – Paul Sammon

Had the original timeline run its course, we would have had ‘Dangerous Days’. However, the death of Scott’s brother resulted in a shift in reality, resulting in a film that was never meant to be, in memory of a reality that would never return.

Now we can understand the emotional resonance Blade Runner evokes within the viewer. Like the windmills in Batty’s rooftop soliloquy, the film stands as a monument to a former reality.

Like replicants' fondness for photos—a desperate attempt to hold on to moments forever lost—we too, find ourselves yearning for fragments of time that slipped through our grasp.

Deckard: “Memories. You’re talking about memories.”

When we are reminded of people, places and things of the past, we feel an emotion which we classify as nostalgia. However, this word doesn't accurately capture the full extent of the experience. It’s not a yearning for former times. It is the dawning in awareness that our reality has changed.

As this understanding grows, we realize that our former reality, or part of it, must die. This may seem bleak, but much like Roy Batty’s final words, it is a moment of existential epiphany.

In the context of Blade Runner’s production, this epiphany was reached by both replicant and director during that rain soaked finale.

Roy Batty’s struggle with and acceptance of mortality resulted in the “Tears in rain” soliloquy.

Ridley Scott’s struggle with and confrontation of his brother’s death resulted in the film Blade Runner.

Neither would have existed were it not for their ultimate realization:

As the rain-soaked cityscapes of Blade Runner unfold, the film becomes a mirror - reflecting not only the paths of what could have been, but also the emotional intensity embedded in its creation. Ridley Scott's decision to direct Blade Runner, driven by the untimely death of his brother, intertwines with Batty's opposition of his four year lifespan. The tears in rain, symbolic of both personal and existential loss, resonate as a poignant metaphor for the nature of our own narratives.

Blade Runner stands not only as a monument to a former reality but as a mirror reflecting the untrodden paths of what could have been — a yearning for a reality that never unfolded, which exists within the celluloid frames and also in the recesses of our own consciousness.

This brings us full circle to our original question:

If our reality changed, how would we know?

Remember the lost moments of your past.

The memories you recall are the monuments of your former realities.

For Galina

♥