Doyle is bad news - but a good cop

THE FRENCH CONNECTION

1971

Why watch it:

It’s a brutally realistic portrayal of cops in the 1970s

It continually upends your expectations, surprising you at every turn, right up to the end

The main character is one of the most complex and fascinating ever shown on film

Memorable scenes:

Picking your feet in Poughkeepsie

Subway cat and mouse

Intense chase

Returning the wave

That ending

Themes examined:

The very thin line between cop and criminal

Obsession

The hazy definition of justice

“What about you Sal, are you everything they say you are?”

There are many memorable phrases in the French Connection, but this one, spoken over a pile of heroin, sums up this electrifying movie.

Nothing is as it seems, and the characters are anything BUT what they say they are.

This is a movie from a different time: Before political correctness, the internet, even cell phones. This was how problems were dealt with. It’s fascinating, but also incredibly brutal.

It’s a cops’ cop movie. Thing aren’t explained, they just happen. It’s a film that doesn’t hold your hand. Much like a detective on a three day stakeout, you’re expected to observe, learn, and join the dots. You need to get your ass to work.

So what is this movie about and why should you care?

The story is based on a real life case which happened in New York through the fifties and sixties. The actual police officers involved in the case – (Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso) worked on the film. They served as technical advisors and even appeared in small roles in the film. Their contributions to the script, specifically the dialogue, make it a film which is unparalleled in its realism and aside from the bar slang, the movie holds up to this day. Never before had the cold, dirty streets of New York felt this real

As is in the title, the movie opens in France. Within the first five minutes, a man is shot in the face and killed. The silent assassin, coldly taking the bread from his now dead target, shows you that this is not the type of movie in which you can expect anything to be explained or to expect that good will win out. This is real.

This opener sets the tone of the film, a callous murder, completely at odds with the scenic locale. This is a theme throughout the movie, subverting your expectations, usually in an abrupt and brutal manner.

Santa Claus in Brooklyn

We aren’t in France anymore. It’s here that we see the star of the film – not the characters, but New York itself. Bear in mind that this film came out in the early seventies, and everything that had been seen before it portrayed America as the land of opportunity, where dreams come true. What brings us to America is a scene like a bad dream: a man dressed as Santa Claus running through a decaying shit hole, catching and beating the piss out of a drug dealer. This is definitely not the America that had been shown by Hollywood before. This city is dirty, corrupt, and nothing like we thought it was.

Picking your Feet in Poughkeepsie

The first of many memorable scenes in the movie introduces us to Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle and Buddy ‘Cloudy’ Russo, two narcotics bureau detectives working on a stakeout. (From here onward referred to as Popeye and Cloudy).

This scene gives an indication of what is to come – expect the unexpected.

Next we see Popeye and Cloudy interrogate the suspect with a routine that gives you an insight into how they would get confessions out of criminals.

This goes beyond the well-known good cop / bad cop style of interrogation. What we see in this scene is the suspect, bloodied and beaten, being put through the psychological ringer. Cloudy, the more straight forward cop, is asking typical questions, but Popeye, all wrath and fists, is asking nonsensical questions:

“I’ve got a man in Poughkeepsie wants to talk to you. He says you picked your feet. You ever been to Poughkeepsie?”

To explain it in detail takes away from the meaning of the scene, but you can see that in Doyle with his bizarre questions and violence, are a threat to the suspect. Not wanting to be beaten further, he answers Cloudy’s questions willingly, as long as it keeps Popeye from him.

As the scene finishes, you can even see Cloudy turning away, hiding the smile on his face as Popeye busts the suspect.

The madness of that scene is at odds with the earlier scene in France, leaving the audience bewildered. This brutal and confusing world has no shallow end, and this is only the beginning.

From here, you see more of Popeye’s abrasive, ruthless character: “Never trust anyone.” he says after uttering other racial epithets when discussing Cloudy’s knife wound. This is followed by Popeye asking Cloudy to go for a drink and look out for “bad guys” – this coming from a racist thug who beats people in his day job.

If he is looking for bad guys, then what do the bad guys look like compared to him?

In the later nightclub scene, we are reminded of the clash between what we see and how it is. Amid the lively environment, well dressed drinkers and upbeat music, Popeye locks onto a table of suspicious looking people. We hear an ominous, painful straining of chords over the music. It’s as if the music is an insight into what’s going on inside his head. This is a man that has an obsession bordering on psychotic, and he’s a cop.

The glitz and glamour of America has something else beneath it, something rotten.

Popeye sums this up in terse dialogue:

That and this movie is definitely wrong.

Part of what makes this movie seem so real is the documentary film style. The grainy, grabbed shots give it a dirty, real to life feel. It’s the polar opposite to the stylized Dirty Harry, which was released shortly after this.

Movie detail: Cloudy throws a straw hat onto the back shelf of the car – a real life tactic used by police to signal to other law enforcement officers that they are working undercover.

After being introduced to Popeye’s captain (the real life Popeye, whom this movie is based on – Eddie Egan) we also see how the rest of the police force view Popeye. Mulderig and Klein (the real life Cloudy – Sonny Valentino):

Mulderig: “His brilliant hunches cost the life of a good cop.”

We are never given additional details on this, however judging by Popeye’s methods, it can’t be far from the truth. He is a drunken, violent, racist man, who frequents places which you would normally associate with criminal types. Is this the hero of the story? The bar he leaves: a dive underneath a bridge, looks like the armpit of New York. The signs are all wrong; he’s more like a cockroach than a cop. How did this man ever get a badge? Does New York hire cops like this, or are cops shaped this way by this urban hellhole?

This idea is hinted at shortly after when Cloudy jimmies a door lock with a card. Could this suggest a criminal past? Or, in this world, perhaps the cops are required to have the same skills as the criminals in order to catch them, but if that’s the case, then what’s stopping them from being dirty?

A man’s home is his castle, and Popeye’s apartment, much like the man himself, is a shambles. It also serves to contrast the two cops: Cloudy is poised and professional, turned out and ready for action. Popeye is handcuffed to his own bed, most probably having abused his position as a cop to take the bicycle girl home with him. As Cloudy looks through Popeye’s scrapbook, he comments on both the book, and Popeye:

Cloudy: “This scrapbook is like you, a mess.”

This really brings up the question of why – why is Popeye a cop? How did he become one? Moreover, why is he so obsessed with bringing justice to others at the expense of his own existence?

Cloudy: “Do you want the red or the white?”

Popeye: “Pour it in your ear.”

Popeye’s obsession with bringing criminals to justice is explored in the fine dining scene.

You can see him watching the main bad guy - Charnier. As he stands outside the upper class restaurant, we see a back and forth between the characters – the French suspects dining, and Doyle freezing out in the brutal New York winter. The difference between the two groups cannot be stressed any further – escargot vs. rubbery pizza. Wine vs. coffee, which we see Popeye tip out onto the frozen concrete – judging by Popeye’s taste, we can only imagine how bad it is, yet the bad guys are the ones inside. Could this be the reason for Popeye’s obsession? The look on his face, the determination to bust the French Connection, there’s something beneath the surface, simmering.

This level of obsession is finally vindicated – not for Popeye, but for the audience at this point – we see the testing and grading of the heroin: “Absolute dynamite.”

“He’s everything they say he is”

This world is on a knife edge. Had Weinstock made the deal in an hour, as suggested by Sal Boca, they would most likely have gotten away with it – all of the respectable, by the book law enforcers are blind to the deal. Only Popeye, driven by a maniacal obsession can see that something is going down. What does this say about policing drug crime?

“I’m sitting on Frog One”

The sequence which follows this holds up the good and bad guy for comparison. The game of cat and mouse played across the streets and on a platform subway between Charnier and Popeye shows that the two could not be any further apart. With the contrasting footsteps alone, we see the difference between the two men: Charnier, elegant and in control; Popeye, frantic and desperate.

The tension of this scene is brought to ahead when Popeye is foiled – for the one and only time in the movie. The final gesture by Charnier, in which they finally acknowledge each other, is a memorable one, and echoed dramatically later in the film.

“The one that followed me on the subway, he’s our biggest problem.”

As Popeye and Cloudy are thrown off the case for a lack of evidence, we see the grim reality of policing then and in some ways now. Both sides are working in the dark, not knowing what the other is doing, but they know that their paths will inevitably cross. The subsequent assassination attempt on Popeye, shows the randomness and acts of desperation perpetrated by both sides.

As Popeye is returning home, now off the case, a sniper opens fire, missing him and hitting an innocent bystander.

Thus begins one of the greatest car chases ever committed to film.

Film fact: When filming this scene, they had no permits, they did this for real.

There is no music, and nothing is done for artistic effect. What you get is cold, brutal reality: the roaring of the engine, the shriek of the brakes and the rush of the train. This is punctuated by ear piercing gunshots and screaming. The chase is not sexy or stylized. It’s real, how it actually would be – frenetic, painful, and desperate. Added to this, we see what it’s like in the minds of these people.

The runaway train, signifying Doyle’s actions, out of control, and reaching the end of the line.

The crash which ends the chase results in one of the most controversial scenes in the movie, one which caused the filmmakers much concern as to how it would be perceived by the audience. Niccoli, exhausted, injured, and with nowhere to go, is confronted by Popeye. They lock eyes for a second, not a word of dialogue between them. Popeye has his man dead to rights, but he collapses against the rail - the only time in the movie we ever see Doyle falter. Niccoli turns to run, and is shot in the back.

This is no glamorous or choreographed death scene. An unarmed man, of no threat to Popeye, is shot in the back. This is not justice, this is murder. However what has happened in this scene is an invisible transition. As viewers, we have watched the chase with baited breath, urging Popeye to capture the assassin. At the moment they lock eyes, we are completely on Popeye’s side, we are complicit in the murder. We are now on the runaway train that is Popeye’s actions, locked in until events come crashing to an end.

Just a cold reality, similar to the NY winter that pervades the whole film.

“That car’s dirty”

As the screw tightens, we see an interesting scene – minor at the moment, but takes on added significance when looked at as a whole.

Cloudy comes face to face with Sal Boca in an underground car park. Though the location is drab and uninteresting, what is going on beneath the surface is fascinating.

Both men are playing roles that are the complete opposite of their characters – Sal Boca is playing the suave, relaxed guy, with everything under control, when in reality, he is the jumpy, paranoid dealer that sees police in his soup. Cloudy plays the bumbling fool, pretending to lose his ticket, when he, alongside Charnier, is one of the most put together characters in the movie. It’s an act of absurdity. By now both men will have seen each other, recognized each other, and circled each other, yet they maintain this facade, an exercise in absurdity. They must know on some level that they will one day act their real roles before each other, but that day is still to come.

During the car drop scene you can see that the streets are disgusting, but the American flag is draped everywhere. Is this the land of opportunity? Is it everything that they say it is?

As they stake out the car, the undercurrent of strings gives the impression of the steam on the street, pressure constantly building.

The failed bust does nothing to dull Popeye’s belief in the case, stating with certainty: “That car’s dirty.”

How can he know this?

Mulderig, the more by the book cop misses this, as does everybody else. It’s only through Popeye’s gut feeling that they have any chance of breaking the case. In this war, the line here between cop and criminal is blurred. The rest of the police in this outfit don’t think on the level of Popeye, it’s as if he is on another level of understanding, all because he barely acts like a police officer. Is this what is needed in the drug war? What does that say about the ideas about justice, fairness and morality?

Having played their hand, the only thing left for the police to do is take in the car and tear it apart. During the following scene, there is one shot in particular, which really shows Popeye’s character.

The car is raised, and we see Popeye for a split second. The look on his face draws a parallel with Friedkin’s other work, Exorcist. What we have here is a man who is possessed, but possessed by what? He knows that there is something in the car, even though it remains hidden. But what is it that is telling him this? Is it his cop’s intuition? His criminal leanings? Or is it something else? Even the audience hasn’t seen anything in the car, so what is the reasoning for his obsession? Popeye’s captain berated him earlier for not bringing in results in previous cases, so earlier experiences can’t be the reason, so it seems that Popeye has a level of intuition borne of his understanding of the criminal mind, most likely because he is in bed with it.

Popeye’s obsession with the car leads to the eventual discovery and unraveling of the French Connection. Interestingly, as Irv opens the rocker panels, the sound of the drill echoes the sound of the music as Popeye and Cloudy are staking out Boca – maybe a coincidence.

Charriere: “I was told these things happen in New York but one never expects it.”

Cloudy: “That’s NY.”

A simple line which says much about the story.

“I saw him. I’m gonna get him.”

We are now in the end game.

Earlier in the movie the majority of the film focused on the activities of Popeye and Cloudy. In this penultimate sequence, again expectations are subverted and we see things unfold from the criminal point of view, with no idea what the police are going to do.

The deal is done with no dialogue, a smile symbolizes it’s done. This sequence is pure cinema, the final details revealed through a slow close up of the money being placed in the car.

The next shot is the most iconic of the movie – as Boca and Charnier drive away, the police spring their trap.

Popeye replicates the wave which Charnier used on the subway. This must have been burning in Popeye’s mind, – sleepless nights, thinking about it.

During the final shootout Popeye ignores the main group, instead going after Charnier. Sal Boca, surrounded by the police, meets his fate at the hands of Cloudy – not stylized or memorable, a quick and brutal end, the camera looks on him for a second, similar to the earlier shot of the traffic accident, and with that, he’s not a player anymore, just a statistic.

After all of the buildup, the shootout is followed only briefly. Our finale is elsewhere.

As Popeye hunts down Charnier, it’s almost as if we see into Popeye’s mind: gun drawn, surrounded by destruction; nothing else matters except justice.

Popeye’s and Cloudy’s approaches couldn’t be more different – Cloudy, runs from cover to cover, Popeye on the other hand, is out in the open, obsessed to the point of foregoing self-preservation.

When he sees a figure in a doorway, there is no hesitation. An empty warning cut short by his own gunshots.

When confronted with the death of Mulderig, Doyle does not even react, his sole focus being Charnier.

Popeye is not even talking to Cloudy anymore. This is no longer a police operation. It’s beyond justice, something else, something more sinister. Even if he brings Charnier to justice, does it justify his actions? Violence? Racism? Murder? Or is it something deeper than that? A reason to be? His purpose? Does he need to see Charnier behind bars so that he can vindicate himself? At this moment there is no line between cop and criminal. If Charnier ends up behind bars, where does that leave Popeye?

This leads us to the controversial ending. Even if Popeye arrested the devil himself, the ending wouldn’t satisfy his, and now our thirst for justice. What we are left with instead, is an enigmatic image of Popeye heading into the final room, with us left outside.

A single gunshot rings out, and then we cut to black.

You are left wondering, who was it?

What happened?

Is that it?

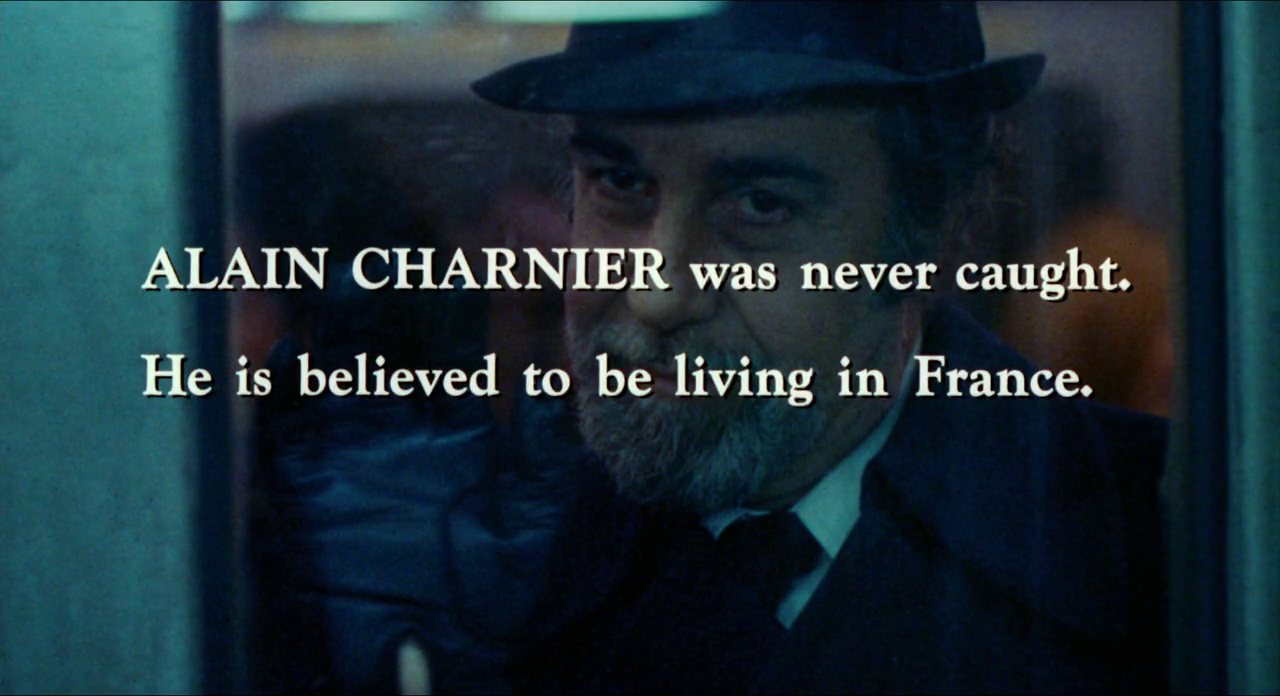

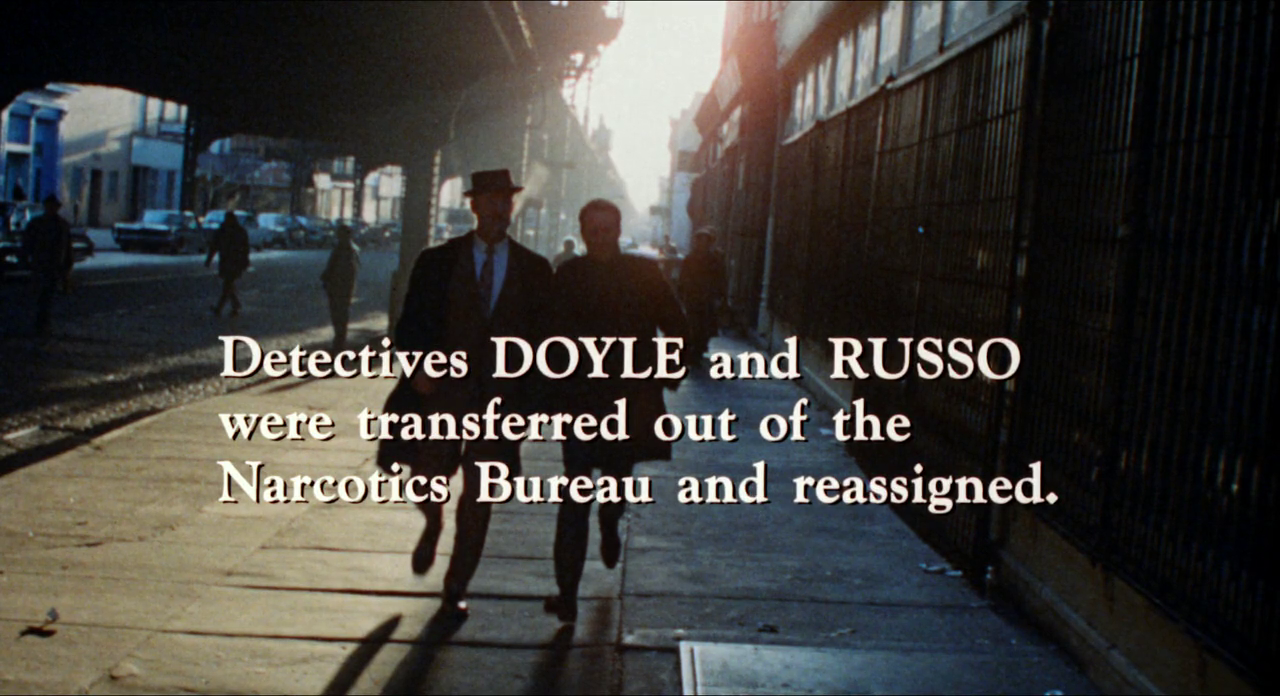

A few short cards tell us the consequences. Of those that do see punishment, Deveraux, the least guilty of all those involved, gets the longest sentence. Charnier, Doyle’s number one target, escapes.

Though it can seem infuriating at first, the ending is best appreciated looking at everything that built up to it.

The characters, their actions, and the events were chaotic and so realistic, that if things had ended in a neat bow, it would have flown in the face of everything that happened before it.

Had Charnier been apprehended and sent to jail, this would not have been enough for Popeye. Had he been tortured and killed, this still wouldn’t have been enough either. The entire final scene is like a manifestation of what is in Popeye’s head – it doesn’t even feel like justice, more like revenge for something only understandable to Popeye. And with revenge, there is no end, no balance. With Charnier’s escape, Popeye’s rage will continue to burn.

Looking at it this way, the movie really couldn’t have ended in any other way. This isn’t your typical Hollywood movie, and by that, it shouldn’t have a typical Hollywood ending.

The final card states the following:

This leaves us wondering – Cloudy, with his professionalism would fit in anywhere, but what in the hell would Popeye do?

What does this ending say about policing, about justice as a whole?

Is it everything we think it is?